text Roelof Kleis‘Next year we’ll be celebrating 50 years of nutrition research in Wageningen,’ says professor of Nutrition, Metabolism and Genomics Sander Kersten. ‘If you review the high points, this study by Katan stands out, for both scientific and societal reasons.’ Fat expert Kersten is in his office. There is a still life hanging on the wall featuring a garden table loaded with fatty foods: bottles of vegetable oil, nuts, avocados, coconuts and so on. ‘Made for a TV programme about fats that I worked on.’ There are no products with industrial trans fats in the picture. In the Netherlands, trans fat was removed from all foods long ago. ‘That social problem is a thing of the past. Which is what makes this a success story.’

‘I had checked 10 times to see whether I had filled in the figures correctly’ – Ronald Mensink, discoverer of the harmfulness of trans fat

To see where the story starts we have to go back to the 1980s, when the Wageningen researcher – and later professor – Martijn Katan was asked by the Dutch Heart Foundation exactly what kinds of fatty acids margarines contained. ‘The reason was an article in the British Medical Journal, which said that margarine can contain fats with trans-fatty acids which are bad for the heart. The director of the Heart Foundation, Bart Dekker, especially wanted to know what was in diet margarine, because the foundation recommended them.’

The now emeritus professor Katan speaks animatedly from his home in Amsterdam about the study that followed. It went on for three years. Katan scrutinized not just the diet margarines but ‘the whole fat shelf’ in the supermarket. It turned out there were no trans fats at all in the diet margarines. ‘But the cheap, hard margarines, deep-frying fat and baking fats contained vast amounts of that trans fat. And there were some very weird compounds in them too. I’m a chemist by training and I was fascinating by all the strangely altered fatty acids you consume with your food.’ A second conclusion was that no one really knew how these fatty acids worked. It was generally assumed that they could not do any harm, says Katan. But was that true?

Cholesterol

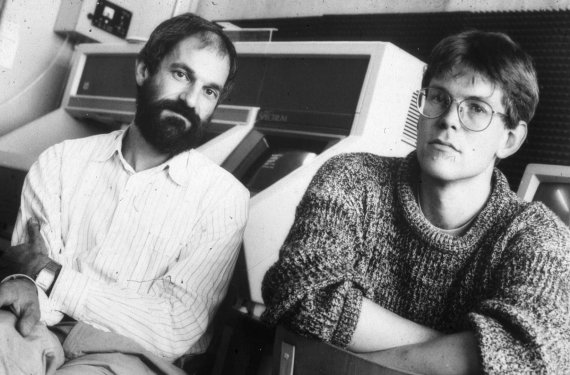

Five years later, in 1987, Katan had enough funding to answer that question. The Heart Foundation allocated one of its grants to a PhD study and Ronald Mensink, a Wageningen graduate in Nutrition Science, was taken on to do it. ‘I had actually wanted to do medicine but I lost the lottery for places twice,’ says Mensink in his soberly furnished professor’s office in Maastricht. So he went to Wageningen, where his interest in medicine was reflected in the emphasis on nutrition, physiology and metabolism in his studies. Mensink had already worked for Katan for a while and Katan wanted him and no one else for this project.

‘The main theme of the study was the effect of monounsaturated fatty acids on blood cholesterol levels,’ says Mensink. It was known that polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as the linoleic acid in sunflower oil, had a beneficial effect on cholesterol levels and thus on cardiovascular diseases (see inset). But little was known about monounsaturated fatty acids such as the oleic acid in olive oil, for example.

Sensational

Mensink conducted three intervention studies. Fifty to sixty test subjects followed specific diets for several weeks and their cholesterol levels were carefully monitored using blood tests. The first two experiments generated articles in The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine. But the sensational finding came from the last experiment, which focused on the composition of the monounsaturated fatty acid. And this is where trans fat comes into the picture. Unsaturated fatty acids come in two forms, cis and trans. In lay terms, the fat molecules are bent and straight respectively. To make it easier to process liquid fat (oil) in foods, it is partially hardened, and this changes the shape of part of the unsaturated fat – cis fatty acids turn into trans fatty acids. Mensink’s research revealed that this change of shape has a big impact on the way the fatty acid functions biologically. Trans fatty acid greatly increases the amount of bad LDL cholesterol in the blood, while lowering the amount of good HDL cholesterol (see inset).

Scoop

‘Heart failure is now mainly only the cause of death among the very elderly’ – Martijn Katan, Ronald Mensink’s PhD supervisor

Katan could hardly believe his eyes when he saw the first results. ‘I said: Ronald, are you sure you haven’t switched anything around?’ But Mensink was sure about that. ‘I had checked 10 times to see whether I had filled in the figures correctly on the computer or whether there wasn’t a mistake somewhere. Could those trans fats have come from anywhere else? But that was impossible: the body doesn’t manufacture trans fats.’ Katan: ‘It was completely watertight. We had a result that nobody had expected.’

The New England Journal of Medicinesmelled a scoop when the article was submitted at the end of 1989. Under pressure from the editor-in-chief, the study’s conclusion was even beefed up a bit: the effect of unsaturated trans fatty acids on health is at least as harmful as that of saturated fat. Katan: ‘I can still remember that I was about to go on holiday when the lady from the New England called. The editor-in-chief himself thought it was better to put it like that. And he was pretty much a god! So I thought: okay then. It was not unreasonable; it was more that I was too cautious. They even added an editorial asserting that there was a lot wrong with those trans fats.’

Worse than butter

The editors of the New England were right to follow their hunch. The article took the world by storm. ‘ We had half the world at our door,’ recalls Katan. ‘The American media zoomed in on the margarines. Margarine had been promoted as good for your heart for years in the US, and yet they were full of trans fat. And now that trans fat turned out to be worse for you than butter, with its saturated fats. The food industry, which used a lot of hardened soya oil that was rich in trans fat, dug its heels in. “This can’t be true. Those guys on the other side of the Atlantic don’t know how to do research.” American researchers wrote sceptical articles about our study.’

But it was true, as repeat studies in Wageningen and elsewhere showed. The renowned Harvard professor Walter Willet presented the ‘smoking gun’ in 1993: an epidemiological study which revealed that nurses who consume a lot of trans fats have more heart attacks. Katan: ‘Then the shit really hit the fan in America.’ He remains modest about the lifesaving effect of the trans fat study. ‘It is just one of the contributions made by science to cutting the number of heart attacks. Heart failure is now mainly only the cause of death among the very elderly.’

A quiet revolution

‘The Dutch food industry removed trans fat from its products of its own accord’

All the negative publications about trans fat led to Unilever in the Netherlands – rather quietly – removing all the trans fat from its products. Genuine science for impact. ‘What is particularly satisfying about it for me,’ says Katan, ‘is that the risk of a heart attack has gone down without people having to do anything themselves. All too often, St Matthew’s law applies in nutrition and health: to those who have shall more be given. In other words: already healthy people adopt even more healthy habits. It was different this time. It wasn’t just the graduates with good jobs who bring their kids to school by bike that benefitted, but the less highly educated too. Because no behaviour change was called for: the food itself was changed.’

Food was changed in the Netherlands, at least. In other countries it took quite a lot longer before the new insights found their way into legislation, says Kersten. In the US, the Food and Drug Association (FDA) only decided in June this year that no trans fat should be used in food. ‘Internationally, there has been massive opposition. The EU only passed a resolution on trans fats at the beginning of this month. The maximum level of industrially produced trans fatty acids in food products is to be set at 2 percent. All products must conform to this by 1 April 2021. So that is how long this kind of process takes. The legislation doesn’t have many implications for the Netherlands, since the industry has removed trans fat from its products of its own accord. But in other places, in eastern Europe for instance, some food products are still full of trans fat.’

The trans fat study had some undesirable consequences too. Yes, the study has saved lives, says Katan. ‘But the use of palm oil has been greatly stimulated as a result. And a lot of rainforest has been felled for that. Another consequence is the drop in margarine consumption. Margarine became suspect, especially in the US. Globally, people are eating less and less margarine. And that is a pity, because soft, trans fat-free margarine is very healthy.’

Follow-up research

Ronald Mensink left after his controversial PhD graduation ceremony (see inset) to take up a postdoc position at Maastricht University. Since 1999 he has been personal professor of Molecular Nutrition there, focussing on fat metabolism. Cholesterol is still central to his work. ‘But here we look more at the effects of vascular function. Does the condition of the blood vessels improve or worsen, and does that have an impact on cognition, in the brain for instance?’

Meanwhile, in Wageningen, the trans fat story has a sequel. Because although it has been irrefutably established that trans fat is harmful, we still don’t know why that is. This question has always interested Kersten, even now the dietary problem has largely been solved. ‘The purpose of science is not just to solve problems, but also to understand how things work.’ So four years ago he appointed a PhD candidate to try to find out what trans fat does inside cells. The first scientific article on this has been published.

Fat, cholesterol and health

The kinds of fatty acids we eat influence the levels of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ cholesterol in our blood, and thus our health. Cholesterol is a fatty substance that the body needs as a building block. Transport in the blood vessel is provided by special proteins in what are called lipoprotein particles. Those particles are mainly found in two forms: LDL and HDL, standing for low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein. The ‘bad’ LDL raises the risk of cardiovascular disease because it causes arteries to get clogged up. A protective effect, by contrast, is attributed to HDL.

Fatty acids influence the distribution of cholesterol between LDL and HDL. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and the cis type of monounsaturated fatty acids lower the bad LDL and are therefore good for the heart. Saturated fatty acids and the trans type of monounsaturated fatty acids do the opposite and are therefore harmful. Trans fatty acids are formed in the food industry when vegetable oils are hardened. They also occur naturally (in small quantities) in animal fats such as fatty meat and butter.

PhD without a thesis

Ronald Mensink was the subject of controversy even before his revolutionary article about the harmfulness of trans fat came out in The New England Journal of Medicine. The top journal claimed exclusive rights and demanded that Mensink’s already printed thesis, which included the article, be withheld until after publication in the journal.

As supervisor, Martijn Katan did not want to deny the top journal its scoop, but postponing Mensink’s PhD graduation was not an option either. So the then rector Van der Plas made an exception to the rule and allowed Mensink to graduate without making his thesis available to the public. Only the examining committee got to read it. The WUB, forerunner to Resource, gave this extensive coverage, drawing the attention of the press. ‘Thesis remains closed book’, ran the front-page headline in the national newspaper NRC. ‘The room was full of journalists who hoped to pick up a snippet from that magic chapter,’ recalls Mensink. In vain: the most sensational bit of the thesis wasn’t mentioned during the defence. ‘That had not been agreed, but everyone could sense that it was a sensitive issue.’ The article came out in The New England five months later, but by then nobody was interested in Mensink’s thesis. He was left with 200 copies on his hands. ‘I just threw them in the waste paper container.’

New series: Wageningen discoveries

What especially significant results have come out of a century of Wageningen research? Resource is going to explore this scientific legacy in a series of stories. New instalments will appear online at irregular intervals, and will be announced in the magazine. Kicking off with this story about trans fats.