Henk Meeuwsen is installing microphones because he is hunting for bird sounds. © Guy Ackermans

After talking for an hour, the room is suddenly filled with the chirp of a skylark. It’s a ringtone. A little later, Henk Meeuwsen says that on his previous phone he used to have a different bird for each contact. ‘So I knew exactly who was calling.’ There are other clues in the room that this is where the soundman lives. A stuffed kingfisher stands on the sideboard. A photo on canvas of a marsh warbler hangs on the wall. And there are a remarkable number of birds on the Christmas cards. ‘I try and keep it all in check,’ explains Meeuwsen. ‘Or else the whole room will be full of birds before you know it. There’s more to life than birds.’

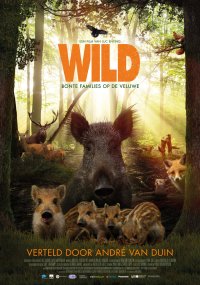

Although… Henk Meeuwsen, GIS researcher at Environmental Research, is undeniably the Netherlands’ leading nature soundman. He built up that reputation steadily over the past 20 years with his CDs, apps and numerous appearances on the nature programme Vroege Vogels. Early next month, the new nature film Wild will confirm his mastery of this particular discipline. The film by the Ede nature filmmaker Luc Enting turns the camera on the Veluwe nature area. Wild follows the lives of foxes, wild boars and red deer, with supporting roles for birds such as the buzzard, raven and black woodpecker. Meeuwsen was responsible for the nature sounds, as he was previously for the film De Nieuwe Wildernis. This earned him a prominent place in the film’s credits.

The sound recordist is proud of this. It is recognition of the significance of his contribution to the film. ‘Sound is incredibly important in this film. Imagine if you didn’t have the nature sounds. There’d be nothing left. It doesn’t work without the sounds of nature.’ Sound adds atmosphere to a film. That applies to all films, but especially to nature films. Nature does not have dialogue that gives direction to the images. Instead, the sound creates depth and ambience. In nature films even more so than in ordinary films, sounds are composed, as Meeuwsen’s working method makes clear.

Sound design also involves composing the background noise, such as a rustling tree.

Dubbing

Nature films are dubbed from start to finish. ‘I basically get sent a silent movie,’ explains Meeuwsen. ‘I watch this silent film and have to select the appropriate sounds. That’s the first stage. For example, I might see a group of red deer grazing ‑ hinds with calves. They are on dry heathland with open woodland in the background with some sturdy Scotch pines. Then I ask myself: what would you hear? What’s the time of year? Has the chiffchaff already returned, or the tree pipit? A skylark might be singing here. And over in the wood a coal tit, a finch and a tree creeper. Then I’ll look for fragments containing those species.’

That is time-consuming. Meeuwsen estimates that it takes him at least an hour to select the right sounds for every minute of film. After the selection stage, the sound designer adds these noises to the film track and fills in and aligns the sound as required. Meeuwsen loves that creative teamwork. Then the film music and commentator’s voice are added. Together, they determine the film’s sound and atmosphere. ‘Sound design also involves composing the background noise for instance, such as a rustling tree or gurgling water. The sound of nature is made up of different layers that you use to compose a cohesive whole.’

If no one hears anything special, I’ve done a good job.

Growling wild boar

Meeuwsen enjoys a lot of freedom in his compositions. ‘If you’ve done it well, no one will hear it or notice it. But everyone hears the mistakes. That’s the paradox: if no one hears anything special, I’ve done a good job.’ Meeuwsen takes a lot of the sounds he uses from his archive, which is a pretty impressive one after 20 years of recording sounds. Even so, he visited the Veluwe dozens of times to record new sounds for Wild. ‘For example, I had recorded red deer bellowing 10 years ago in the wood. But then I saw that the red deer in the film rushes were standing out in the open. And that sounds totally different. Woods have different acoustics and people hear that. I want it to be just right so then I have to go out and find a new sound.’

Sometimes those field trips resulted in more than just his intended goal. Take his recording of the deep growl of a wild boar. ‘I didn’t even know this existed. It was a very deep, ominous sound that a boar made close to a microphone I’d set up. This turned out to be the sound they make if they find something rather suspicious. I’d never heard it before.’ Or take the sound of a buzzard close to its nest with young. ‘I wanted the begging call of young buzzards in their nest. When I played back the recording, in addition to the shrill begging calls I could also hear a kind of internal groan from the parent every time the bird flew away. I don’t know what it means but of course that sound is in the film.’

Meeuwsen spent about 18 months on Wild. He wasn’t working on it every day but it was always in the background. He finds it nice work but also quite a commitment. ‘It does put pressure on you. You have to perform, to deliver. You have to be available all the time and that ties you down. After two films, the film world has lost its novelty value for me and I want to spend more time on my own things. I like being creative and my own boss.’ As in the BirdSound Europe app, which will eventually have the sounds of all European birds. And if the BBC calls and says they are off to Africa for six months and want him as one of their crew? ‘Ah — well then I’d have to think about it.’