Illustration: Rob de Winter

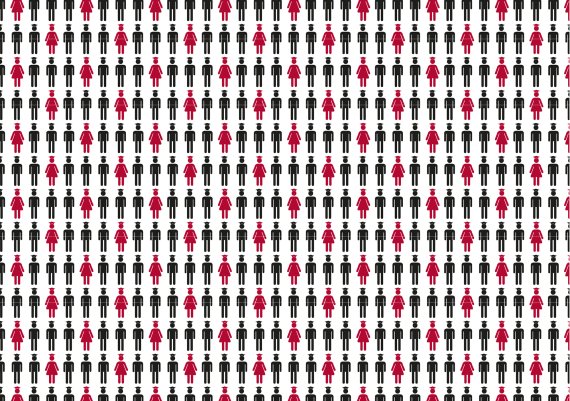

The proportion of women at Wageningen University & Research goes up every year. Last year 57 percent of first-year Bachelor’s students were women. Two years ago there were more female than male PhD graduates for the first time. Of the total staff last year, 48.6 percent were women. But it is a very different picture higher up the organization. The higher the pay scale, the more unequal the men-women ratio. Only one in four managerial staff are women.

Tenure track was introduced in 2010 to improve career prospects for young university scientists. Within this system they can climb the ladder in twelve years from a starting post as assistant professor to a personal chair. As long as they perform well enough, of course. And on tenure track their performance is assessed using objective, quantifiable criteria. Promotion therefore no longer depends on the subjective opinion of a professor. In theory that should give men and women equal chances of promotion. But is that what is happening in practice?

Rate of promotion

Martha Bakker of Land use planning chair group and Maarten Jacobs of Cultural geography scrutinized the situation at the behest of the department of Corporate Human Resources. They compared the chances of promotion for men and women in the four years before the introduction of tenure track with those of the four years after it. They looked at the promotion of young researchers to the ranks of assistant professor, associate professor and ultimately personal professor. ‘We looked at promotion from the bottom up,’ explains Bakker. ‘Every employee has a position on the ladder. If they move up from one year to the next, you can call it a promotion. We did not take into account people coming in from outside.’

Bakker and Jacobs used the figures they got to calculate the rate of promotion: the number of promotions in a year divided by the number of people on the rung of the ladder from which the promotions took place. This produced some remarkable results, which were published in PLOS ONE. First of all, the assumed disadvantaged position of women was not reflected in their rate of promotion, which was already slightly (though not significantly) higher than that of men before the introduction of tenure track.What is more, the influence of tenure track is clear to see; after 2010 the promotion rate of women is 64 percent higher than that of men. Note that this is a comparison of the speed at which men and women climb the ladder: in absolute terms, the number of women reaching the higher echelons remains a lot lower than that of men.

Catching up

‘That 64 percent is certainly a big effect,’ Jacobs acknowledges. But it is not easy to interpret the figures. ‘In any case it suggests that the introduction of tenure track has a systematic impact on the chances of promotion and that this works to women’s advantage.’ But do women on tenure track now really have higher chances of promotion than men? Bakker and Jacobs doubt that. To start with, they point out the ‘catching up’ effect. Some of the women were probably on too low a scale and that is rectified faster with tenure track.

Besides, says Jacobs, women scientists, might just be better. ‘If it is true that it was harder for women to get jobs here, then it is logical that the women who do work here are a little bit better at their job, on average. That’s because a woman has to be better to get in, in the first place. But that is speculation.’

The higher rate of promotion for women is not the whole story. Inequality crept in as soon as new people came in on tenure track. In 2009 the internal pool of potential candidates for getting onto tenure track – young researchers and PhD candidates – consisted of equal numbers of men and women for the first time. Since then women have been in the majority. But this is not reflected in tenure track appointments. In the first four years after 2010, 53 men were appointed and 34 women.

Gender bias

One thing is clear: more women reach the top with tenure track than without it. But does tenure track therefore create gender equality? Bakker and Jacobs modelled various scenarios to show how long that takes. ‘For equal numbers of men and women you will have to wait until some time in the 22nd century,’ says Bakker. ‘Former rector Martin Kropff always said: tenure track is our way of going about emancipation. It turns out now that the system is not designed to create gender equality.’

This system is not designed to create gender equality

Director of Corporate Human Resources Ingrid Lammerse adds a footnote to this. ‘It is not the aim of tenure track to achieve gender balance, but to improve the career prospects of young scientists. For the gender balance we drew up the Gender action plan three years ago. That plan focuses largely on raising awareness of the existence of gender bias.’ In the past few years just under 300 leading managers have taken part in workshops looking at bias. ‘Part of the workshop is a test to study your own bias,’ explains Lammers. What comes out is that 85 percent of the participants have a slight bias in favour of male leaders. Including me.’

The question is, then, how can you get more women on board in spite of this? Lammerse: ‘Through more targeted recruitment, better searches and by actively approaching women. By keeping the text of advertisements gender-neutral and not sounding so pushy. Women are more modest than men.’ A mentor programme has been set up as well, and a book of female role models was published recently.

Positive discrimination

This does not go far enough for Bakker, though. ‘I favour positive discrimination, such as what the NWO does with the Aspasia grants for fast-tracking women towards posts as associate professors. You could do something like that within the university too, using leftover funding from the ‘gender fund’ for instance. Funnily enough, women themselves are often against positive discrimination, because they feel it’s insulting. But then they don’t take into account the fact that a woman scientist has already had to perform better than her male counterpart to get to the same rank. Women often hold themselves to stricter standards than necessary.’

‘Positive discrimination is not our policy but sometimes you can deliberately choose in favour of a woman,’ responds Lammers. ‘Otherwise you will never achieve a more equal men-women ratio. I can imagine, too, than when you are recruiting you might want a woman for the sake of the balance on the team. Not enough women? Then you need to improve your search techniques. But the bottom line is quality; we don’t make any concessions on that.’