Begin twintigste eeuw trok de Landbouwhogeschool in Wageningen veel planterszonen uit Nederlandse-Indië. Foto Archief W.S.V. Ceres

Text Alexandra Branderhorst photos Kees Hopmans

‘We formed a really close group. The International Club was like a living room for us: open every evening,’ says Kees Hopmans, who studied Tropical Irrigation at Wageningen between 1961 and 1970. The International Club was launched in 1958, specially for international students and interested Dutch students such as Hopmans who wanted somewhere to meet each other. More and more foreign PhD students began coming to Wageningen in the 1950s, most of them from rich oil-producing countries, as well as some from India and Suriname. ‘The Netherlands had agreements with certain countries for people to come and do PhDs in Wageningen. The PhD students themselves came from better-off families. They were a bit older and many of them already had families, who often accompanied them to the Netherlands,’ says Hopmans. The Dutch student societies were too immature for these students, so they needed a meeting place of their own.

Prinses Beatrix opens the International Club’s new clubhouse on Rustenburg in 1962. Photo Harry Pot, National Archive / Anefo

Exuberant

At first, the members of the International Club used to get together in the foyer of the Junushoff theatre, but in June 1962, the municipality provided the club with quarters of its own on Rustenburg in the town centre, and Princess Beatrix came to Wageningen for the ceremonial opening of the clubhouse. In the early 1960s,

Hopmans was the only Dutch member of the six-person board of the club, with an Iraqi chairperson and other members from India, Egypt and Suriname. A lot of the members came from these countries, but there were also a few from other countries such as South Africa, Indonesia, Israel, Italy and Hungary. Dutch students who were internationally oriented joined the club too.

Most of the music was Surinamese, which made for an exuberant atmosphere

The club was a place where members could have a drink and a chat, or join one of the many activities. There were film evenings, recalls Hopmans, with films like Laurel and Hardy or Peter Pan. At Country Evenings, members gave talks and slide shows about their countries. Children’s birthdays were celebrated at the club, and there was a Social and Cultural Evening every month, with a band and a dance show. ‘Most of the music played was Surinamese. That made for a colourful and exuberant atmosphere,’ says Hopmans. But people could also come to the club if they were having difficulty with their research or studies. ‘There were several professors wo were always ready to help.’

The International Club functioned as a living room for foreign PhD students in Wageningen in the 1960s. Photo Kees Hopmans

Colonial agriculture

Wageningen had been very international for 50 years before the International Club was started. This was due to the Dutch colonies, which needed knowledge about tropical agriculture and forestry. The majority of Wageningen graduates, 63 percent of the 924 students who graduated between 1918 and 1940, got degrees in colonial agriculture or forestry. Most of their fathers worked in the Dutch East Indies as planters or civil servants.

A handful of Surinamese came to Wageningen too, often with a government grant. It wasn’t a fortune. In 1915, the agricultural college sent the minister for the Colonies a handwritten calculation of what a newly arrived scholarship student from Suriname needed for the first month. It came to 368 guilders, including ‘room and board’, tuition fees, boots and a secondhand winter coat. ‘And we get 200, or at the most 250 guilders,’ the note added pointedly.

The deans received complaints about Dutch students walking around the house naked

World War II and the Indonesian war of independence that followed it, put an end to the close links between Wageningen and the Dutch East Indies. In the 1950s and 60s, the Agricultural College cast its net wider, including tropical and subtropical regions all around the world. There was increasing concern about global inequality and new degree programmes were established such as Non-western Rural Sociology. The Dutch-taught science degrees attracted quite a lot of students from Suriname, then still a Dutch colony. In its early years, the International Club had 30 Surinamese members. The Surinamese students eventually started their own society (see inset). The small but steady stream of PhD students from Arab countries dried up when the Netherlands took sides with Israel in its war with its Arab neighbours at the end of the 1960s.

Third world

In the 1970s, development aid really took off. The Agricultural College wanted to help develop the ‘Third World’ too, by training people from these countries. The first English-taught Master’s programme in Wageningen, Soil Science and Water Management, started in 1971 with 20 students. Most of these students came from English-speaking African countries, Latin America, Asia, Turkey, India and Egypt. ‘The students had to have work experience and a job in their own country,’ says Ankie Lamberts, who was secretary for the programme at the time.

It wasn’t always easy for these students to share housing with young Dutch students. Lamberts vividly remembers a student from Malawi proudly relating how he had taught his flatmates how to clean the kitchen. And the dean of students got regular complaints about Dutch students walking around the house naked, something that was deeply embarrassing for foreign students.

There wasn’t much to do here but the International Club was always open

World music

The International Club changed along with the international community. The family living room on the 1960s made way for a more laid-back venue for parties and get-togethers. ‘There wasn’t much to do in Wageningen, but the International Club was open almost every evening, and it played world music, especially African and Latin American music,’ says Ben Onwuka from Biafra, who came to Wageningen in 1975 and did the MSc in Biology between 1981 and 1983. A Country Evening was still held monthly, with food and music. ‘We even organized a Dutch evening once, with clog-dancing.’ The audience consisted of Latin American, African and Dutch students, as well as some older immigrants.

At the end of the 1970s, Onwuka joined the board to help save the club after funds had disappeared. In 1983, with the help of the municipality, the club moved to its current location on the Marijkeweg. ‘The quarters on Rustenburg were not isolated. Because the police station was nearby, we quite often had policemen stopping by because of noise,’ says Onwuka. The monthly bands and the New Year party were popular. ‘After the fireworks everyone would come to the International Club. There was always a live band and then it was full to bursting.’

In the mid-1980s, the International Club nearly went bankrupt. The chair had secretly lent money from the club’s kitty to her Ugandan boyfriend who wanted to start a business in Uganda, says Onwuka. ‘That money, about 30,000 guilders, never came back. Nor did her boyfriend.’ A new chairperson managed to pay off the debts in a few years, although there was a conflict with some ex-board members. Not many of the club members were bothered, however, as long as the parties were fun.

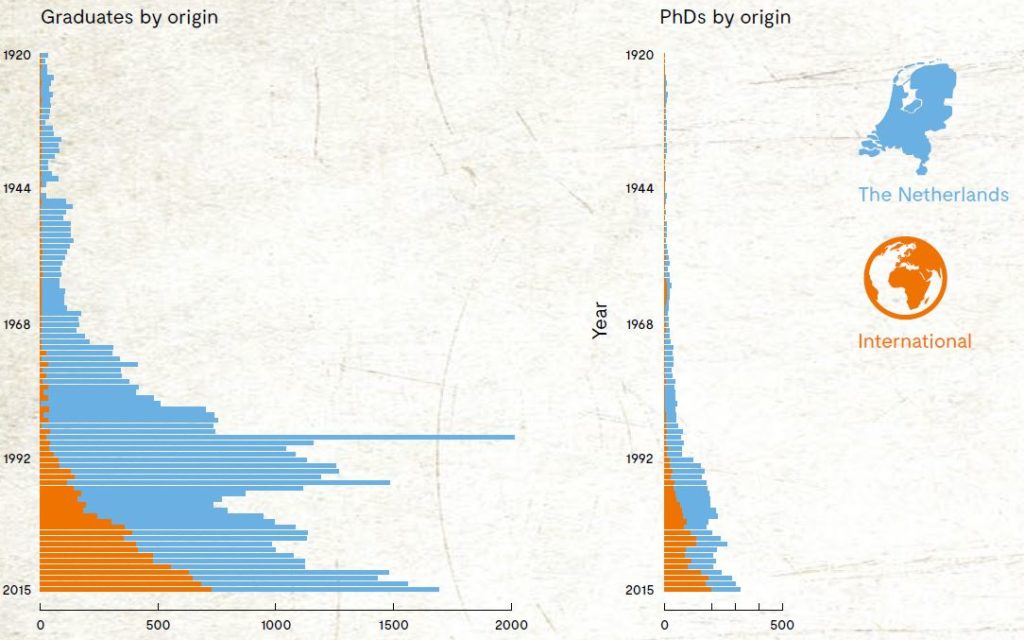

Internationalization in Wageningen picked up speed in the 1990. Now over 40 percent of Wageningen Master’s students and more than 60 percent of the PhD students come from outside the Netherlands.

Bachelor’s and master’s

With increasing interest in the one and only English-taught Master’s programme, Wageningen Agricultural University – as it was known by now – decided to internationalize further. From 1987, three new Master’s programmes were added: Animal Science and Aquaculture, Management of Agricultural Knowledge Systems, and Tropical Forestry. As a result, international student numbers grew and eventually so did the number of international PhD students.

The International Club still attracted a big crowd, albeit a slightly older one. That was why an Indian and an Italian student set up the International Student Organization in Wageningen (ISOW) in the 1990s. ISOW still runs trips and language and dance courses, as well as sports events and parties.

In 1999, Wageningen went over to the Bachelor’s-Master’s system, and since then all the Master’s programmes have been taught in English. The university also intensified its efforts to recruit students overseas. Wageningen graduates became ambassadors of sorts and helped recruit students in their home countries in Asia, Latin America or the Middle East. Students who needed a grant had to apply for one themselves from now on, and the number of African students plummeted as a result. On the other hand, more and more international students were being funded by their government or by their parents.

Now, in 2018, more than 40 percent of Wageningen Master’s students and more than 60 percent of PhD students come from outside the Netherlands (see figure). For most of them the club no longer functions as it used to, as a living room or refuge. The Marijkeweg clubhouse is known more as a place you can go to when all the other nightlife venues close, and an affordable place for graduation parties. At the moment, the club has lost its bar and catering license because the board failed to apply for an extension. If this is rectified in time, the club can celebrate its 60th anniversary in October.

A party at the International Club on the Marijkeweg in December 1984. Photo Guy Ackermans

Links for life

One thing that never changes, however, is the links across borders that are forged for life. Kees Hopmans, who graduated in 1970, benefitted a lot from such links in his international career. During a trade mission to Iraq in 1983, for instance. ‘The consultations reached a total impasse. So then I called Al Azzawi, who was chair of the International Club when I was on the board. The talks got going again thanks to our mediation. Personal contact is so incredibly important.’

| Timeline: | 1958 | The International Club is set up for overseas PhD candidates and other students in Wageningen |

|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Princess Beatrix opens the International Club’s own clubhouse on Rustenburg | |

| 1971 | Twenty students start on the first English-taught Master’s programme in Wageningen: Soil Science and Water Management | |

| 1983 | The International Club moves to a former farmhouse on the Marijkeweg | |

| 1987 | Three new English-taught Master’s programmes are launched | |

| 1999 | WUR introduced the Bachelor’s-Master’s system: all Master’s programmes become English-taught and internationalization really takes off | |

| 2018 | Five Bachelor’s programmes will switch entirely to English from September |

Salsa and roti at Redi Doti

New students get to know the Surinamese society Redi Doti during the 1993 AID. Photo Jacintha Vigelandzoon

Redi Doti was set up in 1967 by and for students with Surinamese roots and other Surinamese in Wageningen. The society rented a premises on the Veerweg, with financial support from Wageningen Municipality, and parties were hosted there monthly. A Caribbean band would play and Surinamese food would be served, such as rice and beans or roti. ‘The atmosphere was different to that of the Dutch student societies, where there was a lot of drinking and a bit of bopping. We have a meal together and dance salsa and merengue,’ says Errol Zalmijn, who studied Biosystems Engineering in Wageningen from 1985 to 1991, and chaired the society for two years from 1987.

Redi Doti – ‘red earth’ in Sranang Tongo – prepared students to go back home. ‘Of course you were in Wageningen with a mission, namely to make use of your knowledge later in Suriname,’ explains Zalmijn. That motive became less important after Surinamese independence in 1975. Besides parties, study evenings and sports events, Redi Doti also ran lectures and discussions on agriculture, development aid and the environment. ‘You had the real party animals, and a hard core of people who were steeped in politics and ideology. Somewhere in the middle was a majority who wanted a bit of both,’ said Zalmijn.

Redi Doti usually had between about 60 and 90 members. When Suriname could no longer provide good funding, numbers slowly dwindled. In 2007, the society gave up the ghost. But many Wageningen alumni were doing good work in Suriname, as farmers or policymakers in agriculture, forestry or nature management. Former Redi Doti member Jim Hok even became minister of Natural Resources, a post he held from 2010 to 2015.