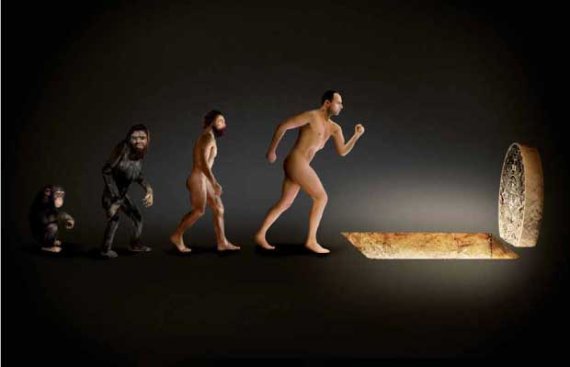

The prominent Wageningen scientists we asked for their thoughts on the fast-approaching end of humanity were surprisingly forthcoming. After all, it is not very credible, is it – the Armageddon predicted by a people that didn’t manage to avert their own annihilation? But the philosophical experiment appealed to these researchers. Just imagine if it were true? How do we look back on the history of humanity then? What have we achieved? Humanity’s peak achievements are closely linked to its deepest troughs, in the opinion of our think tank. Two sides of the same coin. Fantastic that we have succeeded in feeding billions of people, says Louise Vet, for instance. Our technical innovation has facilitated an exponential population growth which the doom merchant demographer Malthus did not believe possible 150 years ago. But Vet sees the flip side of this too: ‘What I am ashamed of is that our expansion has been so unbridled. We are still eating into our resources. We have not succeeded in establishing a cyclical economy based on sustainable energy.’ All four thinkers have these kinds of mixed feelings. Marten Scheffer sings the praises of art and music. ‘In that area human beings have achieved great things, with hardly any negative effects or downsides to them.’ The lowest points, in his view, are ‘war, torture and other mass acts of violence.’ Although nature is by no means all sweetness and light, ‘with our capacities and power structures, we have managed to bring these evils to a whole new level.’ What never ceases to amaze him is that individual people carry this Jekyll & Hyde struggle within them. ‘Nazis practised the fine arts too, while scientific research has shown that you can persuade almost everyone to carry out torture.’ But at least human beings do try, reckons Scheffer. ‘Most religions include old scriptures and practices that aim at keeping evil under control and rewarding good behaviour. So the will is there but we find it hard to put it into practice.’ Michiel Korthals values our ethical efforts to make good victorious, too. ‘Something I still think is incredibly beautiful is the declaration of human rights. If you consider how many different cultures there are, you can call it a miracle that we reached agreement on that. Of course, in many countries no more than lip service is paid to human rights – but at least they exist.’

Hitler

Anyone setting out to evaluate the human race soon runs up against the question: could it have been any different? Are we the lords over our own destiny or has a combination of primitive instincts and ‘modern’ intelligence led inexorably to the world as it now appears? People certainly have a say in the process, but to a limited extent, believes Marten Scheffer. ‘Sometimes you can see that the time is ripe for change, and something is going to happen. But you never know whether it will be a Gandhi who emerges or a Hitler. Leadership can be the decisive factor in how things go for decades.’ Climatologist Pier Vellinga shares the view that the human race has plenty of scope to influence its destiny. ‘There are countless choices open to us, which make their mark on what the world is like in the short or long term. Often there is some kind of limiting factor, such as the availability of natural resources or the vagaries of the climate. But human beings can also step beyond these limits.’ According to Vellinga, there have been various moments when the human race had the opportunity to change the world fundamentally, whether intentionally or not, and usually in a negative sense. ‘Quite recently, when we discovered the CFCs which damage our ozone layer. It just so happened that in the nineteen twenties we opted for chlorofluorocarbon rather than hydrobromofluorcarbons, which break down the ozone layer 100 times faster. If we had gone for those we might have destroyed the ozone layer altogether. Then we might not even have reached the end of the Maya calendar.’ There is a comparable situation with regard to the risk of a nuclear holocaust during the Cold War, says Vellinga. The world could certainly have ended up looking quite different. And if it wasn’t for the Maya Armageddon, the climate was certainly destined to be the next test case. ‘There, too, our choices could be decisive for our future.’

Science

Will the rest of the planet very much regret the demise of the human race? Small chance it will even be noticed, is Louise Vet’s view on that. ‘As a species we are not very significant. If we go under it is of little consequence to this planet. We came into existence at one minute to twelve and we’ll disappear as a species at one minute past. The dominant life form on the earth is the bacteria, with a few insects as well perhaps. Life will just go on as usual for them if humans disappear.’ It is of course something unique that we know this, thanks to the scientific knowledge we have built up. The disappearance of that knowledge with the human race may well be the biggest loss, thinks Louise Vet. ‘From the tiniest to the largest scale, we have gained insight into how the universe works. No other species is capable of acquiring that sort of knowledge in any comparable way. If humanity disappears, that all goes too. That would be sad.’ Philosopher Korthals points out that it has been precisely in the last few decades that sciences has made progress in embedding technical developments in society. ‘All scientific innovations call for norms, or societal embedding. You can see that with something as simple as a mobile phone and how you use it in public. It applies at a more profound level when it comes to food and questions of distribution.’ Marten Scheffer sees an important task in this respect for the currently much maligned social sciences. ‘That is a tremendously complex field, but it is very important because it provides insight into how people react and how we can implement needed changes.’ Pier Vellinga ends up pondering Wageningen’s place in all this. The university has done some extraordinarily useful things for the human race, in his view. ‘The Green Revolution can to a considerable extent be credited to Wageningen. Thanks to that combination of improved seeds, artificial fertilizer and breeding, the world food supply has improved vastly.’ At the same time, Vellinga believes that now that with the end of humanity approaching, we are at a major crossroads as a university. ‘This is the point at which we should ask ourselves whether we should carry on focussing on increasing production. Or whether we should apply our vast expertise to developing sustainable alternatives.’

Bacteria

Finally: imagine that the end of humanity comes in the form of an almighty judge before whom you can make one last appeal. Korthals: ‘I would say: give us another 30 years. Let’s see if we can solve the massive problems we have caused: the unsustainable technologies, unsustainable eating habits, unsustainable agriculture and unsustainable trade. That will be extremely difficult, because global problems are so complex that they cannot be solved in one way alone. There is no silver bullet, even for science. We just have to try everything we can: let a thousand flowers bloom.’

In which era would you most like to have lived?

Marten Scheffer: ‘Personally I am happy when life is simple and I can be out of doors a lot. Instead of that, all sorts of forces constantly drive me to sit at the computer. So it could be that I would have been better off in an earlier period. But then that would mean that half your children could die before the age of one, and that isn’t nice either of course. So actually it suits me very well where I am.’

What tip would you offer a possible new human race?

Pier Vellinga: ‘Make sure your systems don’t get too big and too complex, like ours have done. We are dependent for all sorts of everyday stuff, and even for our food, on producers that often live on the other side of the world. That makes us vulnerable and means a lot of energy is spent on maintaining and monitoring these complex systems. Organize more things on a regional scale. Technology makes that possible in the areas of energy, water and food. With regional, autonomous and self-sufficient communities as the ideal, as the successor to the nation state.

Should we take the Maya calendar seriously?

Louise Vet: ‘The Maya were wiped out as a result of overexploitation of their natural environment. We know that they exhausted the soil and the minerals, undermining the foundation of their civilization. We should learn from that because we are now at a transitional point at which we need to make the right choices. Otherwise the same thing is going to happen to us.’ According to Vet, we should take that warning more seriously than a stone calendar.

Wat What traces of our existence do you hope a possible extra-terrestrial civilization will find?

Michiel Korthals: ‘I am proud of the culture we human beings have produced, and I hope it will not sink without trace. The work of Shostakovich, for example, a Russian composer who died in 1972 – I admire it enormously. In terms of modern art, I would recommend Anish Kapoor, an Indian-born British sculptor. And philosophers have left something behind that is worth retrieving too: Wittgenstein, Popper, Russell, all of the Frankfurt School, John Rawls.’